New investment in wind, solar, and other clean energy projects in developing nations dropped in 2018, largely due to a slowdown in China.

While the number of new clean power-generating plants completed stayed flat year-to-year, the volume of power derived from coal surged to a new high, according to Climatescope, an annual survey of 104 emerging markets conducted by research firm BloombergNEF (BNEF).

Developing nations are moving toward cleaner power but not nearly fast enough to limit global CO2 emissions or the consequences of climate change.

The majority of new power-generating capacity added in developing nations in 2018 came from wind and solar. But the majority of power to be produced from the overall fleet of power plants added in 2018 will come from fossil sources and emit CO2. This is due to wind and solar projects generating only when natural resources are available while oil, coal, and gas plants can potentially produce around the clock.

The volume of actual coal-fired power generated and consumed in developing countries jumped to 6.9 thousand terawatt-hours in 2018, up from 6.4 thousand in 2017. The approximately 500 terawatt hours in new coal consumption is roughly equivalent to all the power consumed in Texas in a normal year.

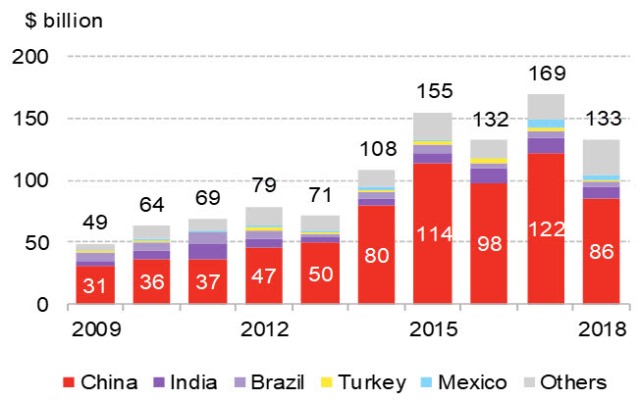

China, both the world’s largest CO2 emitter and largest market for clean energy production and consumption, played a crucial role in the story. Investment in new wind, solar, and other non-large hydro renewables projects in the country fell to $86 billion in 2018 from $122 billion in 2017. That net decline mirrored a $36 billion drop in emerging markets’ clean energy investment figures, the largest ever tracked by Climatescope.

The decline was not confined to China. Inflows to clean energy projects in India and Brazil slipped $2.4 billion and $2.7 billion, respectively from the year prior. Across all emerging markets surveyed, 2018 investment fell to $133 billion, lower than not just the 2017 total but the 2015 figure as well.

Declining costs for solar and wind played a considerable factor in the fall in absolute dollar investment in emerging economies, the report said.

“This year’s Climatescope headline results are undeniably disappointing,” said Luiza Demôro, who manages the project for BloombergNEF. “However, apart from the very largest nations, we did see some important and positive developments, in terms of new policies, investment, and deployment.”

Excluding China, India and Brazil, clean energy investment jumped to $34 billion in 2018 from $30 billion in 2017. Most notably, Vietnam, South Africa, Mexico and Morocco led the rankings with a combined investment of $16 billion in 2018.

Excluding China alone, new clean energy installations in emerging markets grew 21 percent to achieve a new record, with 36GW commissioned in 2018, up from 30GW in 2017. This is twice the clean energy capacity added in 2015 and three times the capacity installed in 2013.

Despite the spike in coal-fired generation, the pace of new coal capacity added to grids in developing nations is slowing.

New construction of coal-fired power plants fell to the lowest level in a decade in 2018. After peaking at 84GW of new capacity added in 2015, coal project completions plummeted to 39GW in 2018. China accounted for approximately two thirds of this decline.

INDIA

India is the top scorer in this year’s Climatescope survey. The nation’s policy framework and copious capacity expansions propelled it to first place in 2019, from second in 2018. The Indian market is home to one of the world’s most ambitious renewable energy targets and has held the largest ever auction for clean power generation.

The Indian government has set one of the world’s most ambitious renewable energy targets by aiming for 175GW by 2022, with 100GW to come from solar, 60GW from wind, and 15GW from other sources. India has also held the most competitive and largest auctions for clean energy power-delivery contracts. These resulted in the procurement of the equivalent of 19GW in 2018 alone. Together, these developments pushed the country to the top of the table on its Fundamentals score and 3rd on Opportunities in the Climatescope ranking.

Renewables, excluding large hydro, account for 81GW of India’s 356GW capacity. Since 2017, capacity additions from renewables have exceeded those of coal. While wind capacity additions of 2.3GW in 2018 were 44 percent below 2017 levels, solar saw its best year to date with 9GW installed. This included utility-scale, rooftop and off-grid capacity. Wind’s 2018 decline was partly due to a switch in the market from a reliance on feed-in tariffs to reverse auctions.