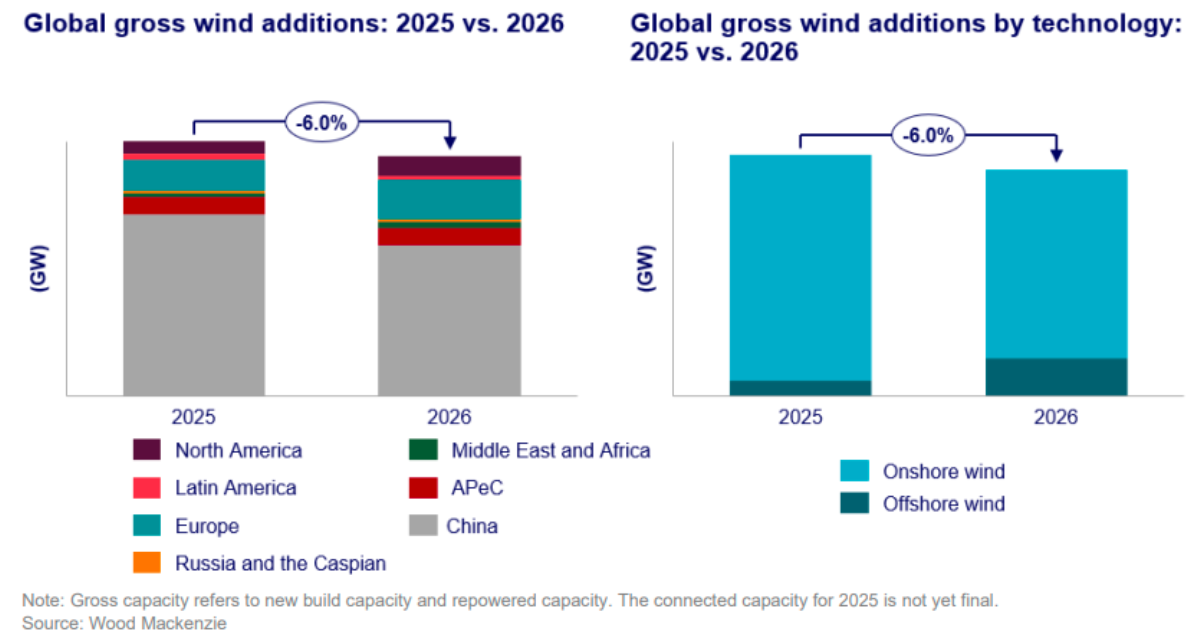

Wood Mackenzie expects strong global wind power connections in 2026, though total additions will fall about 6 percent from 2025, which is set to be a record year. The slowdown in global wind power connections is mainly driven by a year-on-year decline in China following the end of its 14th Five-Year Plan, while the rest of the world is projected to post solid growth.

Europe will account for a large share of new wind capacity in 2026, with Germany standing out due to higher permitted capacity in 2024 and significant onshore wind awards in the same year. Outside China, the United States will remain the largest single market, supported by developers accelerating projects to secure expiring incentives.

As of November 2025, Wood Mackenzie data show that 84 percent of wind capacity forecast for 2026 outside China has already reached final investment decision or is under construction, limiting overall risk. More than half of this capacity comes from projects below 100 MW, which typically have short construction timelines and can still connect within the year.

Offshore wind additions

Offshore wind additions are expected to more than double in 2026, with around 75 percent of planned capacity already under construction. The increase in offshore supply is likely to outpace demand growth, displacing higher-cost thermal generation, particularly gas, and putting downward pressure on power prices.

Offshore wind tender models have progressed from heavily subsidised early schemes to more competitive frameworks as the sector matured. Initial tender models relied on generous fixed-price contracts and feed-in tariffs to support high-cost projects until 2015. As costs fell, tenders shifted toward reduced subsidies and greater exposure to merchant risk under stable economic conditions.

Since 2022, these offshore wind tenders 2.0 have come under pressure, as they failed to adapt to rising costs, inflation and supply chain challenges. This led to tender failures, project delays and offtake cancellations. Governments have since responded with redesigned offshore wind tenders 3.0, offering more supportive terms to ensure projects are not only awarded but also delivered. The EU Net-Zero Industry Act will further reshape tenders by requiring non-price criteria for at least 30 percent of volumes, increasing emphasis on sustainability, resilience and local content.

New tenders

Wood Mackenzie expects 2026 to be a critical test year for these new tender frameworks, with the potential to reverse recent failures and restore momentum, beginning with the UK Allocation Round 7. However, structural timing issues remain. Offtake cancellations are expected to create a buildout lull from 2028 due to long project lead times, risking damage to the offshore wind supply chain.

New tenders are largely targeting grid connections in the early 2030s, raising the risk of renewed supply chain constraints and higher costs if deployment is too concentrated. Wood Mackenzie argues that the most effective policy action in 2026 is to smooth project deployment across years, allowing the supply chain to remain active through the late-decade slowdown and better positioned for the next growth cycle.

Since January 2025, a market-based pricing mechanism has reshaped China’s offshore wind route to market, shifting it from a single phase to a two-phase process. Developers must now first compete for project rights through auctions before securing revenues via tenders or merchant exposure. After large capacity awards under the previous policy in January, offshore wind pipeline growth has stalled under the new framework, with only one auction round announced so far and likely delayed until 2026.

Pipeline expansion is expected to remain subdued through 2026 and beyond due to timing and structural challenges in the new model. Offshore wind projects are not yet viable on a fully merchant basis and continue to require support, but developers must bid in auctions held in the second half of each year for projects scheduled to connect the following year. The requirement to guarantee grid connection within this narrow window, combined with lengthy permitting, design cycles and sea-use approvals, significantly increases delivery risk and uncertainty, dampening developer appetite.

Despite these challenges, offshore wind construction in 2026 is unlikely to be affected, as the existing awarded pipeline is sufficient to sustain buildout for the next three years. However, the new market-based pricing regime weakens offshore wind’s long-term competitiveness in China compared with utility-scale solar and onshore wind.

Looking ahead to 2026, policy support will be critical, particularly for deep-sea offshore wind projects planned over the next decade. Without additional measures, the new framework could begin to influence supply chain investment decisions, technology development, capacity expansion and export ambitions.

US onshore wind heads into 2026 under mounting pressure from policy deadlines, tariff-driven cost increases and evolving market conditions. Under the One Big Beautiful Bill Act and updated IRS guidance, developers must begin construction by July 2026 to qualify for production tax credits for projects targeting 2029-2030 operations, pushing companies to accelerate procurement and development activity.

The definition of “start of construction” is now tightly linked to the physical work test, requiring on-site activity or off-site turbine component manufacturing under binding contracts. Much of this qualifying activity is occurring through behind-the-scenes component-only orders. However, tariff uncertainty is disrupting procurement strategies, leading to uneven order volumes in 2026, marked by pauses followed by bursts of contracting as policy clarity improves or deadlines near.

Permitting challenges are expected to persist through 2026, limiting project buildout and leaving several large projects cancelled or inactive, particularly on federal land. Offshore wind faces added headwinds from stop-work orders under the Trump administration, deepening uncertainty in an already strained sector.

Policy will remain the dominant factor shaping the wind market in 2026, with developers awaiting clarity on foreign entity of concern provisions under the OBBBA, which are unlikely to be resolved early in the year. At the same time, rising electricity demand is becoming a critical counterbalance. Wood Mackenzie forecasts strong peak demand growth through 2030, driven by utility load commitments and longer-term data centre expansion. While much of the data centre demand materialises after 2030, projects to meet that demand must start development now, reinforcing the long-term need for new wind capacity and raising questions over whether policy priorities will shift to support supply growth and energy affordability.

Three decades of steady onshore wind capacity growth have created a growing end-of-life challenge, as an increasing number of turbines approach or exceed their original 20- to 25-year design life. To date, most asset owners have chosen to extend turbine lifetimes to maximise returns while managing rising operations and maintenance costs. However, with a large global wind fleet now older than 20 years, end-of-life decisions are set to have a greater impact on capacity retirements and production declines, particularly as performance degradation accelerates in the final years of operation.

This preference for lifetime extensions is expected to continue in 2026, especially in Europe and North America, where retrofit and partial repowering capabilities are well established. Decommissioning activity has so far been limited and largely driven by early retirement for repowering, supported by policy incentives such as tax credits in the United States and auction advantages in Germany. As a result, decommissioning has not kept pace with the expanding pool of ageing assets in mature markets, leaving the broader end-of-life issue unresolved.

Despite this, Wood Mackenzie highlights a positive trend, with a significant share of global wind decommissioning occurring between 2023 and 2025. Decommissioned capacity is expected to increase further in 2026, mainly involving older turbine models in mature markets. This rise will be driven primarily by repowering, as newer and larger turbines deliver improved efficiency and lower costs, offering a pathway to modernise ageing wind fleets.

Capex

Wind energy capital expenditure showed strong regional divergence in 2025, with costs expected to begin stabilising in 2026, albeit for different reasons across major markets.

In China, onshore wind turbine prices rebounded sharply in 2025 and are forecast to stabilise in 2026. While declining project revenues may continue to pressure developers to push risks onto suppliers, downside price risk is expected to be contained. The Industry Self-Discipline Agreement introduced in 2024 remains in force, and a new government policy issued in 2025 aims to curb disorderly price competition, together limiting further component price erosion.

In Western markets, cost pressures are expected to persist, driven by shortages of specialised labour, elevated interest rates, geopolitical uncertainty and policy risks. Even as material costs eased, turbine prices continued to rise in 2025 as original equipment manufacturers prioritised margin recovery over volume growth. Wood Mackenzie views 2025 as the peak of cost inflation, with gradual easing beginning in 2026.

European onshore turbine prices are expected to plateau through 2027, with only modest declines over the next two years as OEMs maintain pricing discipline. The growing adoption of the 6- to 7-MW turbine class is delivering early scale benefits, but potential implementation of the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism could offset cost reductions, complicate procurement and ultimately increase prices.

In the United States, policy has become the primary driver of costs. Permitting delays, tariffs, tax credit phase-outs and supply chain efforts to restore margins have pushed turbine prices higher since 2022. Ongoing tariff and foreign entity of concern restrictions are likely to sustain volatility, with developers expected to accelerate safe-harbouring of equipment for 2029-2030 projects, placing additional strain on limited domestic manufacturing capacity and potentially driving prices higher if current tariffs remain in place.

After a period of rapid capital expenditure inflation from 2021 to 2025, offshore wind costs are expected to stabilise in 2026 as the sharp increases driven by input volatility and margin recovery begin to level off. While high costs contributed to recent tender failures, market conditions are shifting. Equipment contracts signed in 2026 will largely support projects scheduled to connect between 2028 and 2030, when a wider supply gap is expected to emerge, making further price increases in 2027 unlikely.

The emerging oversupply points to stabilising pricing power rather than a sharp margin collapse, with impacts varying across the supply chain. Turbine manufacturing remains highly consolidated in Western markets, dominated by Vestas and Siemens Gamesa Renewable Energy, both of which continue to prioritise value over volume, limiting the likelihood of aggressive price competition. More fragmented segments, such as foundations, are more exposed, with some suppliers expected to accept lower margins or higher schedule risk to secure volume in 2026.

Suppliers serving multiple end-markets, including HVDC equipment and cable manufacturers, are better insulated due to strong demand from broader electrification trends. As a result, only a limited share of offshore wind capex is likely to face downward price pressure. However, utilisation risk is becoming more pronounced and selective, with factory underuse expected to emerge from 2026.

Supply and demand dynamics are expected to self-correct, as suppliers respond to weaker demand by deferring investments, mothballing capacity and reducing headcount before resorting to price competition. Early signs of this adjustment were already visible in 2025, including Vestas delaying planned blade facility investments in Poland. Price deflation will also be constrained by the fact that much of the 2026-2028 supply is already locked into framework agreements signed between 2022 and 2024, meaning any cost relief will mainly benefit late-stage, uncontracted projects.

Power market reforms introduced in China in 2025, shifting from guaranteed tariffs to competitive auctions and market-based pricing, are accelerating a broader global transition already under way in markets such as Germany. These changes are forcing the wind value chain to prioritise predictable performance, reliability and system-level value rather than pure cost competition. With capture prices declining and supply chain strategies adapting to this new reality, 2026 is expected to be a pivotal year for the sector.

The transition is evident across the industry. Western turbine manufacturers have moved away from price-led competition toward value-driven approaches, emphasising modular turbine designs, digitalisation, AI-based predictive maintenance and improved grid integration. At the same time, leading Chinese OEMs are expanding beyond low-cost offerings to provide integrated solutions, including project development, hybrid energy systems and AI-enabled platforms, while increasing investment in local manufacturing and ESG compliance to strengthen their technology and service credentials.

The ultimate winners and losers of this shift remain unclear. Historically, intense cost competition made margins a zero-sum outcome among developers, governments and suppliers. As revenue structures evolve under market-based pricing, closer coordination across the value chain will become increasingly important. Competition will also extend beyond wind to other generation technologies. Wood Mackenzie expects wind’s competitiveness relative to solar to improve in 2026, particularly in parts of Europe, the Middle East and Africa, as market barriers ease and new tender frameworks are implemented.

BABURAJAN KIZHAKEDATH