An analysis from Ember shows that utility-scale battery storage has reached a transformative milestone, with the cost of storing electricity falling to USD 65 per MWh as of October 2025 across markets outside China and the United States. This signals a major shift in the economics of renewable energy, enabling solar power to be delivered exactly when it is needed and making fully dispatchable clean electricity a reality.

The Ember study indicates that the all-in capital expenditure to build a long-duration utility-scale battery energy storage system is now around USD 125 per kWh. Of this, roughly USD 75 per kWh covers core equipment shipped from China and about USD 50 per kWh goes toward installation and grid connection. These figures are based on real-world projects, recent auction results in Saudi Arabia, India and Italy, and expert interviews conducted by Ember across markets including Australia, Mexico, Romania, Croatia and Türkiye.

An all-in capex of USD 125 per kWh results in a levelized cost of storage of USD 65 per MWh based on the latest project parameters. The decline in LCOS is not driven only by cheaper batteries. Longer lifetimes, better round-trip efficiencies and lower financing costs due to clearer revenue models such as auctions have all contributed to accelerating the cost reductions, Ember’s Kostantsa Rangelova (Global Electricity Analyst) and Dave Jones (Chief Analyst), said.

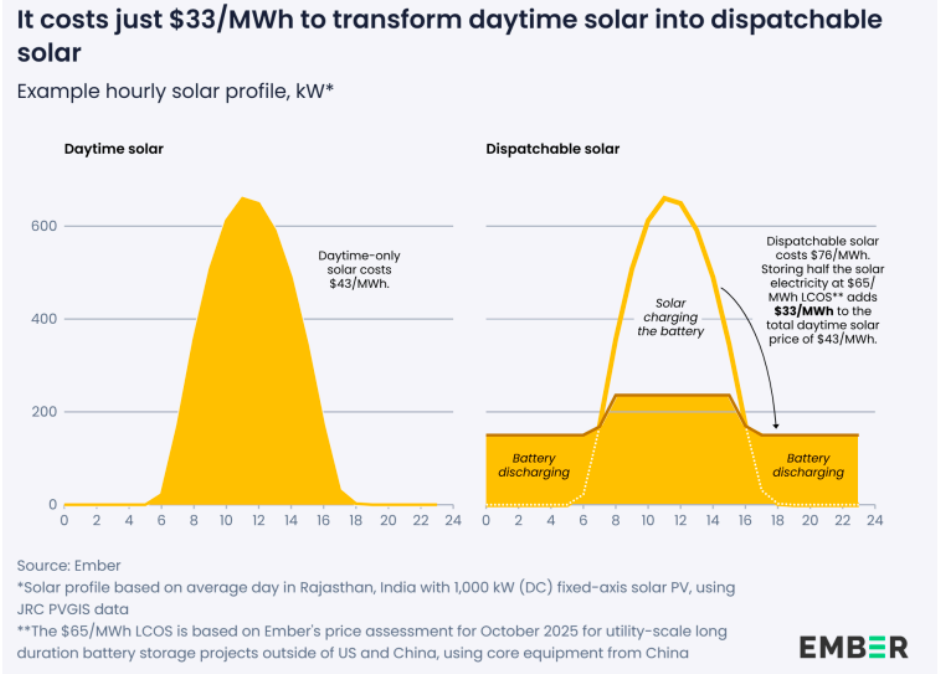

At USD 65 per MWh, storing half of a day’s solar generation for night-time use adds just USD 33 per MWh to the overall price of solar power. With the global average solar price in 2024 at USD 43 per MWh, converting solar into an anytime, dispatchable energy source would result in a total electricity cost of USD 76 per MWh. This marks a significant shift in the economics of renewable power, particularly for countries with rising electricity demand and strong solar resources.

The dip in storage costs follows a 40 percent drop in battery equipment prices in 2024, with trends pointing toward another substantial fall in 2025. Industry experts note that the economics of batteries are changing so quickly that developers and utilities are still adjusting to this new environment. Solar is evolving from a source of cheap daytime power to a fully controllable and predictable energy resource, which represents a step-change for global energy systems.

Core battery equipment, including enclosures, the power conversion system and the energy management system, now costs about USD 75 per kWh for long-duration projects, assuming low import duties. This is based on the price of Lithium Iron Phosphate battery cells, which have fallen to roughly USD 40 per kWh in China as of November 2025. These cells are integrated into enclosures that typically hold five to six MWh of capacity in 20 foot containers. Enclosures account for nearly ninety percent of the equipment cost, while PCS and EMS make up the remainder.

The USD 75 per kWh benchmark applies primarily to large, four hour or longer storage projects. Smaller systems generally receive less competitive pricing. Moreover, four hour systems benefit from ten to fifteen percent lower overall equipment costs because several components are sized to power rather than energy. While extending duration beyond four hours still lowers costs, the marginal savings become smaller.

In some markets, core equipment costs can rise to USD 100 per kWh or higher due to higher tariffs, stricter certification requirements or local content rules. However, in India, local PCS and EMS manufacturing keeps domestic prices competitive with China.

Engineering, procurement and construction services, along with grid connection, typically add about USD 50 per kWh to overall project cost, although this can vary widely. Grid connection fees are the largest variable, ranging from USD 30 per kWh in markets with inexpensive grid access to USD 100 per kWh in exceptional cases. When batteries are co-located with existing solar plants or deployed behind the meter, grid connection costs become minimal.

Overall, the rapid cost reduction in battery storage is reshaping global energy planning. With storage now affordable enough to firm large volumes of solar generation, countries can rely more heavily on renewables to meet peak demand, reduce dependence on fossil fuels and accelerate decarbonization. Solar is no longer limited to daylight hours. It is becoming a round-the-clock, dispatchable resource, marking a fundamental shift in how clean energy will power economies in the years ahead.

Recent auction results across Saudi Arabia, Italy and India strongly support the estimate that utility-scale battery storage projects now cost about USD 125 per kWh.

In Saudi Arabia’s Tabuk and Hail projects, equipment supply contracts awarded in August 2025 were priced at USD 73 to 75 per kWh, while EPC contracts added USD 47 to 48 per kWh, resulting in an all-in cost close to USD 120 per kWh.

Italy’s MACSE tender in October 2025, which cleared at EUR 13 per kWh per year, also aligns with a capex of roughly USD 120 per kWh, based on expert assessments of a USD 70 to USD 50 per kWh split between core equipment and EPC.

The Italian payback period of around eight years, before discounting, further validates this estimate, especially with additional revenue streams available to developers.

India’s 2025 auctions show similar pricing trends, with the RVUNL tender clearing at USD 12 per kWh per year, about 20 percent lower than Italy. However, India’s capex subsidy of just over USD 20 per kWh explains this reduction. Experts indicate current BESS costs in India remain close to USD 120 per kWh, though some bids appear lower due to expectations of future battery price declines.

The cost of core equipment has dropped sharply, falling forty percent in 2024 to USD 165 per kWh according to BloombergNEF. This decline reflects rapid expansion of assembly plants, heightened manufacturer competition and continued reductions in LFP cell prices. Installation costs are also decreasing as systems become more modular and easier to deploy, with integrated PCS units reducing complexity and risk.

Baburajan Kizhakedath